SLO vs SLI vs SLA is not a terminology debate. It’s a systems design problem. These concepts represent distinct layers of reliability thinking, yet they’re often collapsed into a single idea.

When that happens, organizations lose the ability to reason clearly about performance, risk, and ownership. The confusion persists because SLOs, SLIs, and SLAs all reference the same surface metrics: uptime, latency, availability, and error rates.

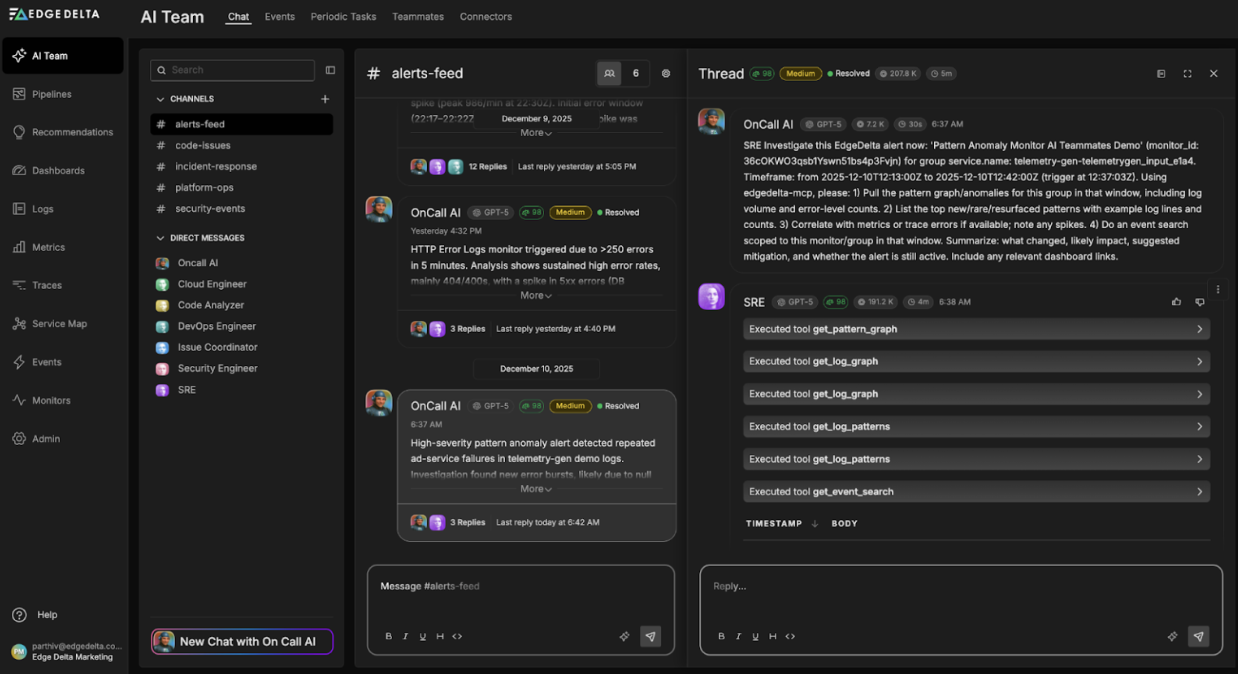

Automate workflows across SRE, DevOps, and Security

Edge Delta's AI Teammates is the only platform where telemetry data, observability, and AI form a self-improving iterative loop. It only takes a few minutes to get started.

Learn MoreTeams talk about these numbers without clarifying whether they’re measuring reality, defining acceptable system behavior, or making external commitments. Over time, that ambiguity hardens into policies, contracts, and incentives that don’t reflect how systems actually behave.

Most reliability failures don’t start with outages. They start with flawed mental models. To understand why confusion between SLIs, SLOs, and SLAs is so costly, these concepts must be examined as a connected system rather than isolated definitions.

| Key Takeaways • SLIs, SLOs, and SLAs operate at different layers. SLIs observe reality, SLOs define internal targets, and SLAs establish external commitments. Collapsing these layers undermines clear reliability thinking. • Most reliability failures start with flawed assumptions. Confusing measurement, intent, and obligation introduces risk long before an outage occurs. • SLIs should measure user experience, not dictate behavior. When indicators become goals, teams optimize metrics instead of outcomes. • SLOs exist to manage trade-offs. They create explicit boundaries that balance reliability with delivery speed. • SLAs must be conservative and buffered. They preserve customer trust by absorbing normal system variability rather than exposing it. |

What Do SLI, SLO, and SLA Mean in Reliability Engineering?

Reliability engineering separates observation from intent and intent from obligation. SLIs, SLOs, and SLAs exist to enforce those boundaries. Each term answers a different question, serves a different audience, and tolerates a different level of uncertainty.

Before comparison is meaningful, definitions must be precise. Without clarity at this level, later discussions about trade-offs, ownership, or accountability collapse into opinion rather than engineering judgment.

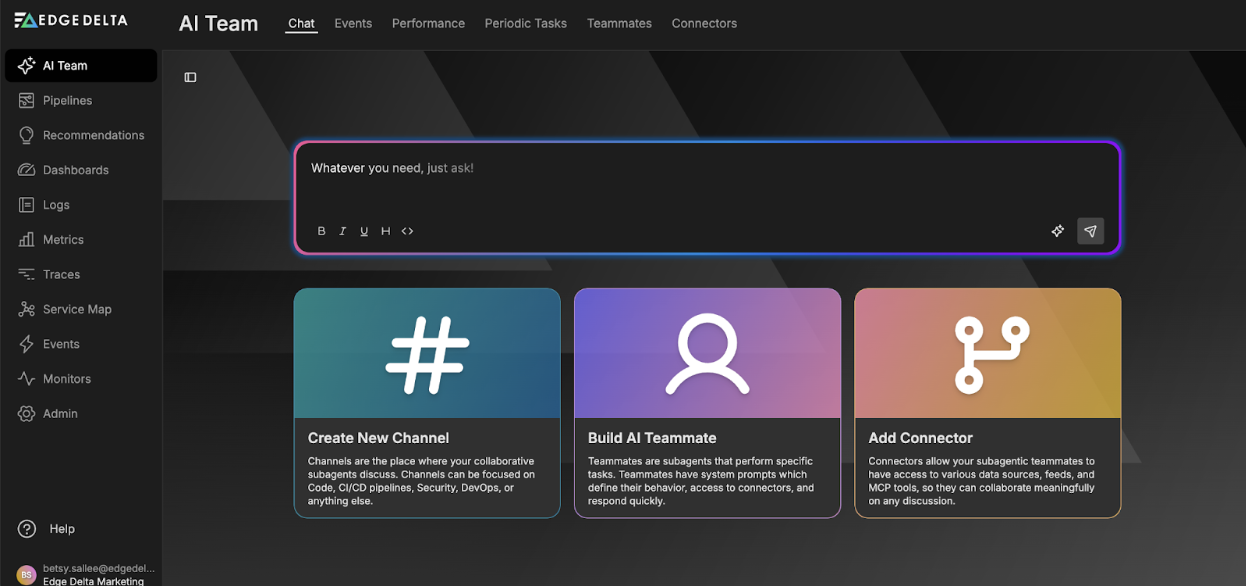

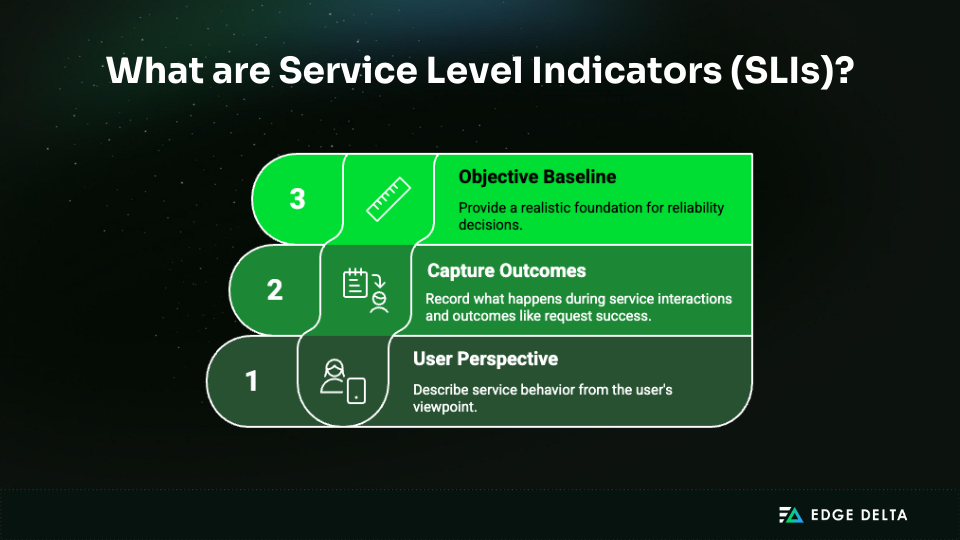

Service Level Indicators (SLIs) as Reliability Measurements

Every reliability conversation begins with observation. Before deciding what should be acceptable or what can be promised, teams must understand what the system is actually doing in production.

Service Level Indicators (SLIs): Quantitative measurements of observable system behavior

SLIs are quantitative measurements that describe how a service behaves from the user’s perspective. They capture outcomes such as request success, response latency, or data correctness.

An SLI does not evaluate that behavior. It records what occurred. This distinction is foundational. SLIs are often mistaken for goals, even though they are not designed to guide behavior.

When teams optimize SLIs directly, they optimize numbers rather than user experience. Used correctly, SLIs provide an objective baseline that allows higher-level reliability decisions to be grounded in reality rather than assumption.

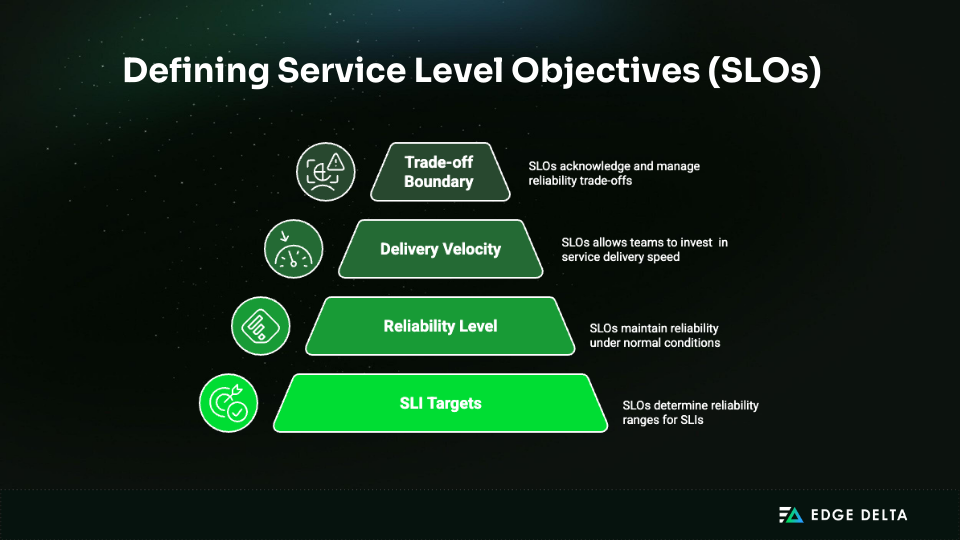

Service Level Objectives (SLOs) as Internal Reliability Targets

Once system behavior is observable, the next question is intent: not what happened, but how much unreliability the organization is willing to tolerate in pursuit of other goals.

Service Level Objectives (SLOs): Target reliability thresholds defined as acceptable ranges for SLIs

SLOs set target ranges for one or more SLIs over a set period of time. They show how reliable an organization plans to be when things are running normally.

An SLO is not a promise of perfection. It is a deliberate boundary that acknowledges trade-offs and accepts that a controlled margin of failure is often more practical than pursuing absolute reliability.

That boundary enables prioritization. When a service operates within its SLO, teams can safely invest in delivery velocity.

When reliability gets close to or goes above the limit, the focus moves to stabilization. Error budgets make this model work by making it clear how much unreliability can be handled before delivery slows down.

SLOs also create a shared reference point for engineering and product teams, reducing subjective debates about when reliability concerns should interrupt roadmap commitments. In this way, SLOs transform reliability from abstract aspirations into an operational control system.

Service Level Agreements (SLAs) as External Service Commitments

Only after observation and intent are defined internally does commitment become appropriate externally. SLAs formalize reliability where it intersects with customer expectation and contractual obligation.

Service Level Agreements (SLAs): External service commitments that define performance expectations and penalties

SLAs are contractual agreements that spell out what kind of service you can anticipate, how that service will be measured, and what will happen if those expectations aren’t satisfied.

Because SLAs often include service credits, financial penalties, or escalation clauses, they must be written with careful consideration of normal system variability rather than best case outcomes.

Unlike SLOs, SLAs are externally visible and enforceable. They are designed for predictability rather than operational nuance. SLAs intentionally abstract away internal mechanics so providers retain flexibility in how reliability is achieved.

Customers don’t need to know about error budgets, deployment risk, or cascading failures. They need to be sure that the agreed-upon expectations will always be met. Well-written SLAs protect both customers and suppliers by making promises that are realistic and build confidence over time.

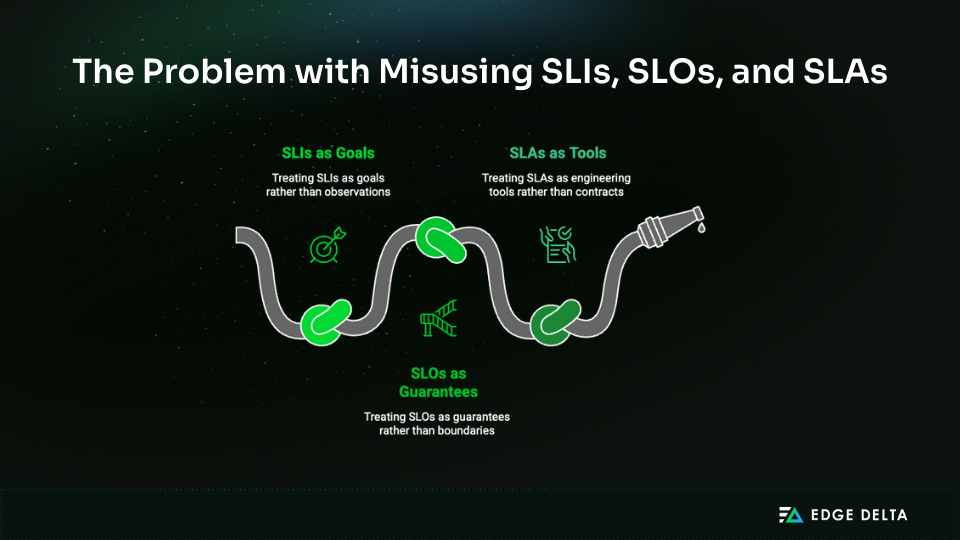

What Goes Wrong When SLI, SLO, and SLA Are Confused?

When these layers collapse, reliability becomes brittle. This is often worsened by inconsistent or poorly normalized observability data across systems. Confusion introduces predictable and compounding failure modes across engineering and business functions.

In this section, we’ll explore some common failure patterns.

Misaligned Engineering Incentives from Incorrect SLO Definitions

SLOs shape behavior even when no one explicitly acknowledges them. Poorly defined objectives quietly rewrite priorities.

SLO misconfiguration risk: Poorly defined objectives lead to misaligned engineering priorities

When SLOs are not linked to user experience, teams focus on following the regulations instead of getting results. Metrics turn into goals, goals turn into rewards, and rewards lead to the wrong job.

Conversely, when SLOs are treated as immutable promises, teams avoid necessary change and accumulate technical debt. In both cases, reliability stops being intentionally managed and begins oscillating between fragility and stagnation.

Customer Trust Erosion from Overly Aggressive SLAs

The cost of confusion is highest at the customer boundary, where expectations harden into perception.

Overly aggressive SLAs: Tighter guarantees increase breach frequency and erode customer trust

SLAs without a sufficient buffer normalize breach. Repeated failures reduce penalties to background noise and undermine confidence. Customers lose trust not because incidents occur, but because expectations were unrealistic from the start.

How Should Organizations Correctly Apply SLI, SLO, and SLA Concepts?

Correct application is not about stricter enforcement. It is about alignment. Each layer must be allowed to perform its intended role without absorbing pressure from the wrong direction.

Using SLIs for Observation, Not Performance Judgment

Observation must precede evaluation, a concept reinforced by core observability principles that separate measurement from interpretation. Without that separation, metrics lose meaning.

SLIs as observations: Indicators describe system behavior without defining acceptability

SLIs should reflect reality as accurately as possible. When they are used as judgment tools, teams optimize numbers rather than outcomes. Used correctly, SLIs anchor reliability discussions in evidence rather than opinion.

Using SLOs to Balance Reliability and Delivery Velocity

Intent enables prioritization. Without SLOs, every incident becomes an existential crisis.

SLOs and error budgets: Reliability targets balance system stability against feature velocity

SLOs turn reliability into a controlled variable. They let businesses move quickly without becoming weak and stable without stopping progress.

Using SLAs to Set External Expectations Without Exposing Internals

Commitment requires abstraction. Customers need outcomes, not internal mechanics.

SLAs as abstractions: Customer-facing commitments should not expose internal reliability targets

SLAs inform customers what they may expect without giving out internal limits, error budgets, or operational plans. This division keeps things flexible and lowers the chance of having to renegotiate as systems change.

When Do SLI, SLO, and SLA Definitions Matter Most?

The cost of ambiguity increases with scale, complexity, and customer exposure. What feels manageable in small systems becomes dangerous in large ones.

Reliability Management for Customer-Facing and Revenue-Critical Services

Customer-facing and revenue-critical systems amplify the impact of reliability failures, where unclear definitions can quickly turn small issues into broader risk.

Customer-facing services: Clear SLIs and SLOs are required to manage reliability expectations at scale

Without clear indicators and objectives, reliability discussions devolve into opinion during incidents. Explicit definitions create shared understanding and faster decision-making under pressure.

Reliability Measurement in Complex Distributed Systems

As systems grow more interconnected, defining reliability becomes harder and more important. This is especially true in environments that demand observability practices for advanced distributed systems.

Distributed systems complexity: Defining meaningful SLIs and SLOs becomes harder as system interactions increase

In distributed architectures, poorly chosen SLIs obscure true failure modes. That confusion propagates upward, weakening objectives and commitments alike.

Conclusion: Why SLI, SLO, and SLA Clarity Is a Reliability Discipline

SLIs observe. SLOs decide. SLAs commit. Reliability breaks down when these boundaries blur.

When organizations don’t maintain these distinctions, measurement becomes judgment, objectives become promises, and promises become liabilities. Clarity restores control. It allows teams to reason about reliability as a system rather than a collection of disconnected metrics.

Reliability is sustained not by dashboards or contracts, but by shared understanding of where observation ends, where intent begins, and where obligation must stop.

Common Questions About SLO vs SLI vs SLA

What is the difference between an SLI, SLO, and SLA?

An SLI looks at how a system behaves, including how long it takes to respond or how many times it works. An SLO tells you what level of that activity is acceptable over time. An SLA makes such expectations clear for customers and spells out what will happen if they aren’t satisfied.

Why should SLOs and SLAs not be the same?

SLOs help direct internal decisions and allow for engineering trade-offs, whereas SLAs are external promises that have to remain stable. Keeping SLAs tighter gives you a buffer that can handle normal system variability without causing frequent breaches.

Are SLIs metrics or goals?

SLIs are metrics, not goals. They describe what happened in the system without judging performance. Goals are introduced at the SLO level, where acceptable reliability thresholds are defined.

Who owns SLOs versus SLAs?

Engineering teams typically own SLOs with input from product stakeholders, since they influence development priorities. SLAs are usually managed by business or legal teams, with engineering support, because they define customer commitments.

When are SLAs required?

SLAs are required when services involve contractual obligations, regulatory expectations, or explicit performance guarantees. They are most common in customer-facing systems where reliability directly affects trust and business outcomes.

Sources: